[One Paper Later] On-demand Container Loading in AWS Lambda

You can also listen to AI generated discussion

Overview

AWS released this paper On-demand Container Loading in AWS Lambda which discusses how they were able to scale their Lambda offering to support container images upto 10 GiB from originail 250 Mib.

Originally, users had to ZIP their code and upload it to S3 to run on Lambda. For each new invocation (especially after a cold start), AWS would spin up a new lightweight VM, pull the ZIP file, and execute it. This worked well because AWS’s global backbone network is fast and 250 MiB is relatively small, keeping cold-start times low (typically ~50ms).

With the move to supporting container images — and large ones, up to 10 GiB — two core challenges arose:

- Network bandwidth: Servicing such large images could overwhelm network capacity.

- Cold start time: Pulling multi-GB images could drastically increase latency.

Despite this, the core requirement remained: keep cold-start times near 50ms. This required significant engineering effort and innovation. For this they exploited three core properties of container images

- Cacheability: The majority of workloads come from a small number of unique images.

- Commonality: Many popular images are based on common base layers (e.g., Alpine, Ubuntu).

- Sparsity: Most files inside container images are not needed at startup.

Architecture

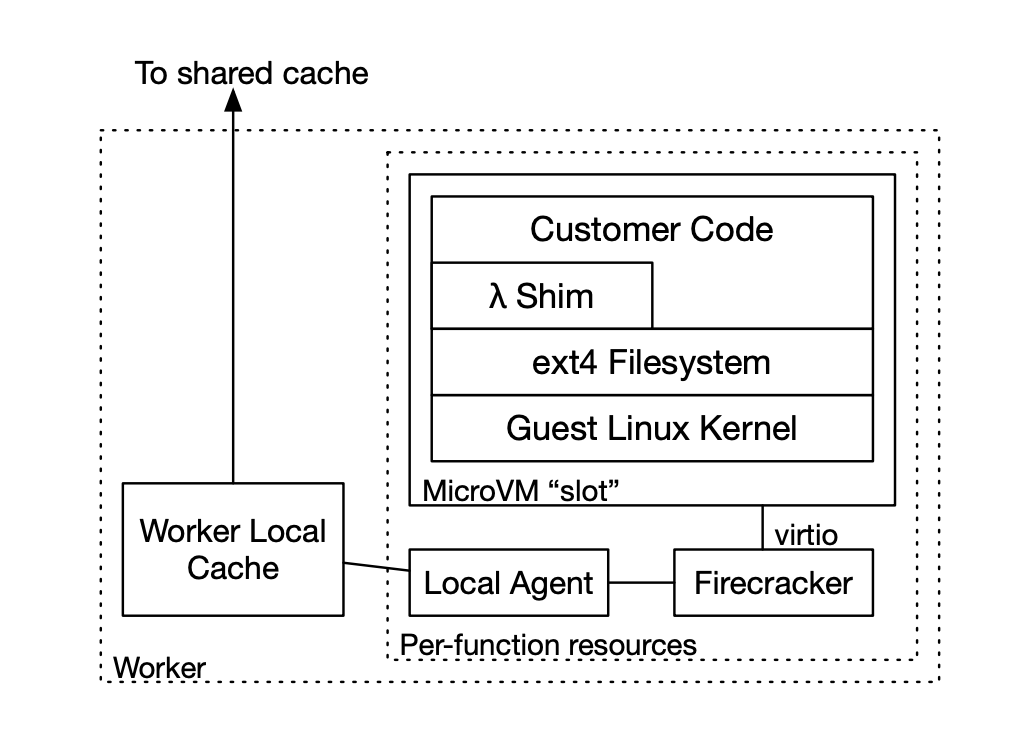

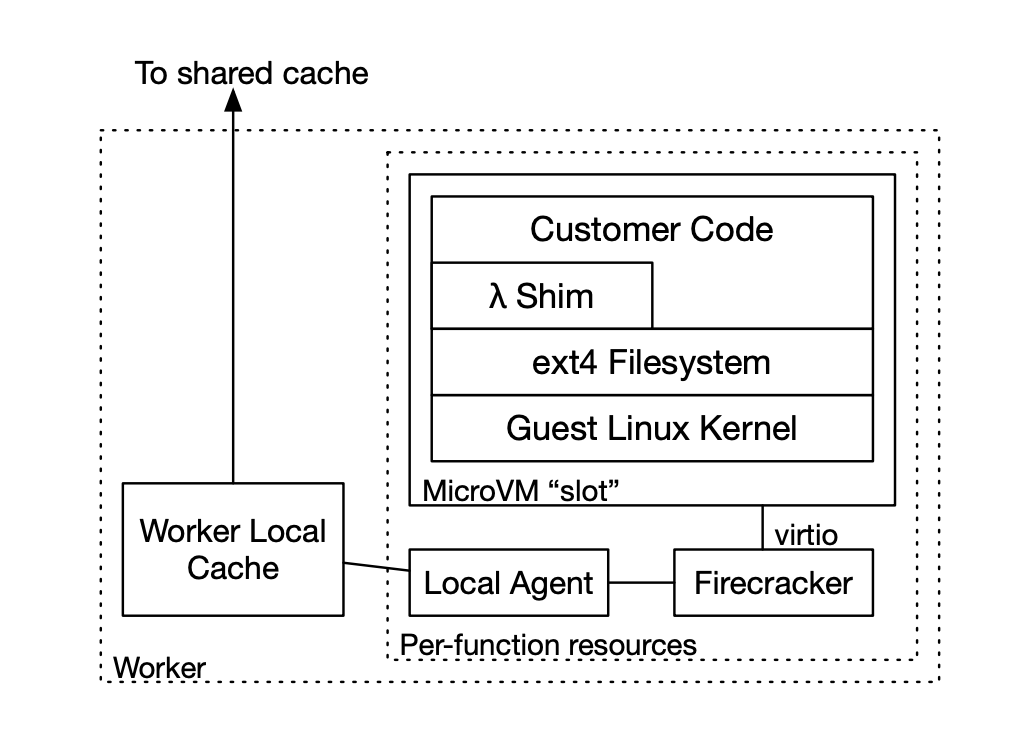

When a user invokes a Lambda function, the request eventually lands on a Lambda worker.

Each Lambda worker can host multiple functions. A local agent process runs on the worker and communicates with the Firecracker VM via virtio, a standard virtual device interface. Inside the VM, this local agent appears as a block device (like a virtual hard disk).

Filesystem Preparation

- When a container image is used for Lambda, at the time of Lambda function creation, its layers are flattened into a single ext4 filesystem.

- This filesystem is split into 512 KiB blocks in a deterministic way — meaning the same input always results in the same set of blocks.

- Each block is individually encrypted using convergent encryption:

- A cryptographic hash (AES-256) of the block is computed (with a salt).

- This allows blocks from identical images (even across users) to be deduplicated and stored only once.

- A manifest stores these hash values and salts and is encrypted using user-level encryption keys.

Storage and Caching

- Blocks are stored in S3 and cached at:

- Availability Zone (AZ) level

- Local agent level (on the worker itself)

- These multi-layer caches are highly effective, serving ~99.8% of requests from cache rather than S3.

Startup and Read/Write Behavior

- When a function starts, it reads only the necessary blocks from the local-agent-backed block device.

- Writes are handled via a copy-on-write mechanism:

- A block overlay tracks page-level modifications.

- A bitset marks which pages have changed.

- Reads to modified pages are redirected to the overlay.

- This ensures the original cached blocks remain immutable and reusable across functions, improving cache hit rates and memory efficiency.

Garbage Collection (GC)

A major challenge in deduplicated systems is safe and efficient garbage collection. Lambda avoids reference counting or centralized metadata to reduce complexity and risk. Instead, AWS introduced a root-based GC model:

- A root is a self-contained manifest and chunk namespace.

- When a container image is processed, its manifest and chunks go into an active root (e.g., R1).

- Periodically, a new root (R2) becomes active, and R1 is retired—serving reads only.

- Active manifests and their referenced chunks in R1 are migrated to R2. Over time, all live data is moved to the new root.

- Once safe, R1 is expired. In this state:

- Reads are still allowed.

- Any read triggers an alarm that pauses deletion and alerts operators, serving as a safety mechanism.

This process ensures:

- No accidental deletion of active data.

- GC bugs have minimal blast radius.

- The system can support multiple active roots to test or roll out GC updates gradually.

While expired roots and chunk duplication increase storage costs slightly, the tradeoff is acceptable—most customer data is updated frequently, and not all data is migrated.

Conclusion

AWS Lambda’s evolution from small ZIP files to massive 10GB container images is a masterclass in system design. By leveraging:

- Deterministic block generation and convergent encryption

- Intelligent caching and copy-on-write overlays

- A root-based, alarmed GC system

AWS was able to maintain low cold start times while scaling Lambda to support modern containerized workflows. This architecture not only optimizes performance and resource usage but also preserves tenant isolation and security, all without disrupting the user experience.

Source